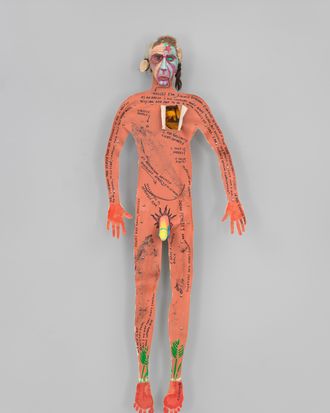

In 1986, Jimmie Durham, a young conceptual artist who had spent much of the 1970s as an activist with the American Indian Movement, was asked by the Kenkeleba Gallery in the East Village to do a self-portrait as part of a group show. It’s a full body outline of “him” in canvas, hanging flat — perhaps, creepily, like a flayed skin — with a painted mask for a face, shells for ears, beads for eyes, braided animal-fur hair teasing out his “Indianness,” and a Day-Glo yellow-and-red cast of a penis jutting out, with comic exoticism. The body is covered in graffiti (or tattoos): “Indian Penises are unusually large and colorful”; “My skin is not really this dark, But I am sure that many Indians have coppery skin.” It all hangs off a wooden combine sculpture of found tree limbs, animal skulls, and furniture flotsam. Today Self-portrait, by turns deadpan, defiant and evasive, is one of his best-known works, and it’s at the heart of his first U.S. retrospective which opened first at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles last spring, before traveling to the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and, finally, to the Whitney, opening this week.

The Self-portrait is hardly straightforward, and far more ironic than heroic, but it plays with his identity and the viewers’ perceptions of that identity with the self-assurance of an insider, even while signaling his ambivalence about it. Durham, 77, grew up in Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas and has always claimed Cherokee ancestry as the starting point for his conceptual investigation and activism. But an identity-politics firestorm has threatened to overshadow his significant achievement and influence, not to mention making the Whitney, already a bit on edge in the wake of the appropriation controversy surrounding Dana Schutz’s Open Casket from this year’s Biennial, skittish.

All this dates back to June 26, when a group of ten Cherokee artists, educators, and leaders published a letter to the website of Indian Country Today, just four days after his retrospective opened at the Walker. The group’s letter claimed Durham was “a trickster” who is “falsely claiming to be Cherokee” and went on to state that he “has no Cherokee relatives; he does not live in or spend time in Cherokee communities; he does not participate in dances and does not belong to a ceremonial ground.” In the ensuing weeks and months he was labeled everything from “The Artist Formerly Known As Cherokee” to the “Art World’s Rachel Dolezal,” and the Walker issued the following disclaimer to the webpage and wall credits of their show:

While Durham self-identifies as Cherokee, he is not recognized by any of the three Cherokee Nations, which as sovereign nations determine their own citizenship. We recognize that there are Cherokee artists and scholars who reject Durham’s claims of Cherokee ancestry.

It was a few weeks later, in July, that I visited Durham in Berlin, at the Schöneberg apartment he shares with his partner of nearly 40 years, Brazilian artist and environmental activist Maria Thereza Alves, whose work often addresses the oppression of indigenous peoples. I’d seen “Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World” at the Hammer but hadn’t met the artist in L.A. because he wasn’t able to make the long-haul flight, due to fluctuating high-blood pressure and the danger of having another stroke.

The Berlin air was thick with humidity, and I was anxious to discuss Durham’s work in his beguiling retrospective: his titular carved-wood series, A Pole to Mark the Center of the World; his idiosyncratic assemblage sculptures (made with industrial machinery; organic materials; and carved heads invoking Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés, his indigenous Mexican adviser and mistress La Malinche, or simply Durham himself); the absurdist performance videos of the artist smashing quotidian objects on a filing desk and a five-hour-long gonzo documentary made by Cristian Manzutto, who followed Durham for nearly a decade; various material explorations of obsidian, rare woods, and animal skins; and an array of self-portraits (including photographic invocations of Alves and Duchamp’s cross-dressing alter ego, Rrose Sélavy). In short, I’ve long found Durham to be one of those enigmatic multimedia wizards like Jean-Michel Basquiat or David Hammons, the contemporary art world’s master of mystique (and, not incidentally, most sly commenter on identity.) He’s everywhere — influencing just about everybody — and, then, nowhere to be found.

“For all I have gained from the bottomless intellect and insatiable curiosity of the man himself, there is so much I do not know,” Anne Ellegood, the senior curator of the Hammer who organized the ambitious exhibition, writes in the introduction to the substantial monograph accompanying the show. It took eight years of persistent negotiations for Ellegood to get the green-light from Durham, who left the U.S. in 1987 and hasn’t lived here since.

“I consider myself really a part of Europe,” says Durham, who is represented by the blue-chip gallery Kurimanzutto. Given the fact that he hasn’t shown any substantial amount of work in the States for about two decades — aside from a few group shows, art fairs, and his inclusion in the famously identity-politics-focused 1993 Whitney Biennial, where he showed a series of weapon-like wall sculptures (dealing with notions of surveillance, the police state, militarization) that were pieced together with vintage gun parts, carved branches, and coyote bone among other sundry items — “At the Center of the World” was a rare treat for countless artists, curators, and critics who could only follow Durham from afar while his work continually appeared abroad at august venues like the Venice Biennale, Documenta, and galleries and museums across Europe and Latin America.

But before he rose to art-world renown, Durham made a name for himself through activism. He fought for land rights and health care and against tribal enrollment with the American Indian Movement, and then as director (from 1974 to 1979) of the International Indian Treaty Council, which was recognized by the United Nations as an NGO in 1977.

But tribal identity in the United States is a highly regulated thing which Durham has always stayed outside of, whether by temperament, critique or, as some activists have insinuated, other less high-flown reasons. The 1990 Indian Arts and Crafts Act (IACA) made it illegal for anyone falsely claiming Native ancestry or tribal affiliation to sell art as such.

First-time violators of the law are subject to a $250,000 fine, five years in jail, or both. After a 1993 profile appeared in Art in America, which quoted him talking about being Cherokee and a “Cherokee artist,” Durham wrote a letter to the editor stating: “I am not Cherokee. I am not an American Indian. This is in concurrence with recent US legislation, because I am not enrolled on any reservation or in any American Indian community.”

Which seemed to settle things — that is, he wasn’t going to play that bureaucratic identity-politics game — until this summer. It likely upped the cultural stakes that the Schutz who-can-talk-about-whose-pain discussion had besieged the Whitney earlier this year, and then, just a few days before Durham’s opening at the Walker, Sam Durant’s “Scaffold,” a sculptural representation of gallows used in numerous state executions — including 38 Dakota men hanged in Mankato, Minnesota, the largest mass execution in U.S. history — was removed from the Walker’s sculpture garden after an outcry from Dakota activists. These protests prompted Durant to de-install the piece and sign over rights to the Dakota people. The executive director of the Walker, Olga Viso, said at the time: “Everyone had agency in this conversation — especially the artist … He does not feel censored.”

In the wake of the Durant dustup, the Walker’s disclaimer for Durham’s show wasn’t surprising, per se, but it arguably just missed — or simply ignored — the core tenets of Durham’s life and work. While they might not recognize him as such, Durham never attempted to enroll in any of the three federally recognized Cherokee tribes — the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians of Oklahoma, or the Cherokee Nation — and his accusers aren’t even asking him to take any actions regarding his ancestral claims.

“He’s an artist and no one wants him censored, no one says he shouldn’t create the art he creates, no one says he doesn’t deserve a retrospective. I’m not saying anything against his position as an artist in the international art world. I don’t want anything from Jimmie,” says America Meredith, a Santa Fe–based Cherokee artist who has become the unofficial spokesperson of this new group questioning Durham’s ancestral claims. “Anaïs Nin had this double life. That’s part of her story, and this is part of Jimmie’s story. I don’t care what he’s done, it’s really common, people do it all the time. He can say any crazy thing he wants to say, he’s an artist, artists do that. But being Native American in the United States is not just an ethnic identity, it’s a political identity and I think what’s going on is a complete unwillingness to understand group identity as opposed to an individual’s identity. It’s a legal and political definition. It’s not romantic.”

But that legal and political definition is itself contentious.

For Meredith, there is “no way” Durham can prove he is Cherokee or of Cherokee descent, but when I asked if she would share the documents ruling out the latter she refused and referred me to Gene Norris, the senior genealogist at the Cherokee Heritage Center in Oklahoma. It took months to track down Norris, but when I finally got him on the phone, he explained that Meredith enlisted him to do an Ancestry.com search of public records (deeds, marriage licenses, articles indicating the names of relatives, information on geographic migratory patterns of families, and population censuses) related to Durham and his family.

“We don’t tell anyone that they are not Cherokee. What we look at is a documentable paper trail,” says Norris, who considers himself “a genealogist who does Cherokee research, not a Cherokee genealogist.” While his paternal ancestors are Cherokee according to family history he, like Durham, will never be recognized by any Cherokee tribe because his ancestors resided outside the Cherokee Nation at the time of the Dawes Rolls, the final lists of people accepted between 1898 and 1914 by the Dawes Commission as members of the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole tribes. Consider it the gold standard in terms of Cherokee tribal enrollment.

“I did not grow up in a Cherokee community, I did not grow up speaking the Cherokee language, I did not partake in ceremonial grounds like the outdoor church, I grew up in Arkansas so I was not brought up in that type of atmosphere,” says Norris, whose family history in many ways mirrors Durham’s. The artist’s childhood wasn’t defined by participating in ceremonies on a reservation, but rather a tight-knit extended family that lived between Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas and wasn’t short on outlaws.

When I asked Norris if it were possible if Durham, by some human error on a census or the Dawes Rolls, could in fact be Cherokee by slipping through the cracks, he admits, “I could not really answer that question. There are families that were not here at the time of Dawes that are Cherokee, but they can document their Cherokee ancestry.” Norris had never heard of Durham before Meredith, his friend of 20 years, asked him to do this research, which Norris claims took a “couple hours” of his personal time. When I asked him if he could cross-reference the Durham family names listed on the rolls — as cited by Ellegood in a lengthy and reasoned defense of the artist’s claims of self-identification for Artnet News— he told me that he “could not do it in a quick time period” and I’d need to pay him to do it officially through the Heritage Center.

“Almost every one of the recognized tribes of the United States use a federally mandated document called a base roll so it’s a paper trail, it’s not genes and chromosomes flowing through your blood kind of evidence,” says Norris, admitting, “The records that we use for genealogy are not meant for genealogy. They are very ambiguous and very incomplete and imprecise but that’s all we have to go by. That’s why records don’t reflect everything. I could be wrong. I just go with what documents I was able to research.”

Norris, to me, seems like a perfectly reasoned and extremely forthright man who was brought into a political argument, which he does not want or care to enter, by a friend. But his honesty is telling in that it highlights the problematic nature of attempting to give or deny anyone a cultural and/or political identity by such fallible methods.

“It is important to recognize that in our fathers’ and grandfathers’ era many light Indians simply passed as white folks. If you can’t get a job as an Indian, and you can if you are white, why admit to being an Indian? Also, birth certificates are usually made out by nurses, which means that a child’s (and his mother’s) color determines his or her race. Therefore many Indians are white on their birth certificates. I think it is hard for young people today to realize that many, many people of color never admitted to being Indian or black. They can’t realize how difficult it was in 1900 and onwards. Do you realize that we were not even citizens until 1924?” asks Kay WalkingStick, the world-renowned Cherokee landscape painter, who first met Durham at his New York studio in 1976 when she was working on a show for the Morris Museum. “There was never any doubt in my mind that he was/is a Cherokee. It is perfectly possible that Jimmie Durham is part Cherokee, and the group searching for proof won’t find a trace of that.”

A couple days after the Walker opening, a lawyer specializing in Indian law like IACA explained to the art blog Hyperallergic that Durham’s retrospective “technically doesn’t run afoul of the law, but it definitely violates the spirit of the law.”

Though he declined to be interviewed for this piece, in his essay for Durham’s catalogue, Comanche author and associate curator of the Smithsonian-run National Museum of the American Indian Paul Chaat Smith writes, “Jimmie Durham is an Indian project. Perhaps all I’m really saying is that even more than needing him, we really miss him. The Red Nation wants him back.”

Clearly Jimmie Durham revels in blurring the line. After leaving AIM in 1979 to focus on his art practice, many of Durham’s early pieces involved his Native American ancestry, often deploying a profoundly ironic sensibility. In Pocahontas’ Underwear he employed the bottom half of a beaded and feathered costume found in the garbage and displayed it in one of his vitrines of “fake artifacts” for his seminal institutional critique On Loan From the Museum of the American Indian (1985) at New York’s Kenkeleba Gallery.

It was also around this time that Durham said, “I am a Cherokee artist who strives to make Cherokee art that is considered just as universal and without limits as the art of any white man is considered. …If I am able to see both Cherokee art and all other art as equally universal and valuable, and you are not, then we need to have a serious talk.”

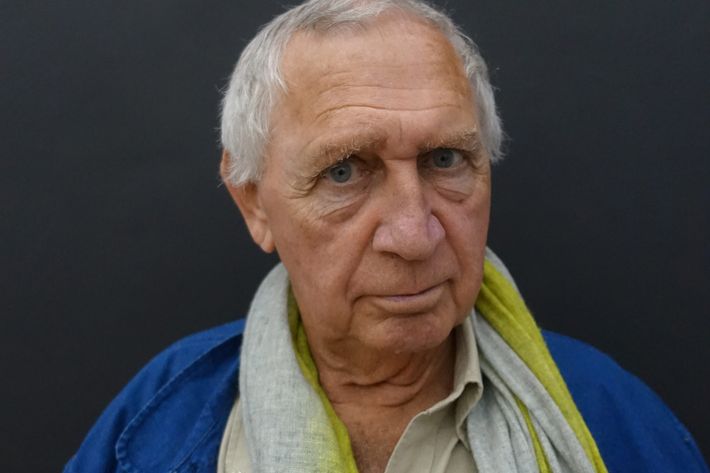

While Durham can be serious to the point of intimidating, I found him light and charming when I finally arrived at his white loft space. Behind a wall of frosted-glass windows, you enter into a small sitting area punctuated by modernist and vintage furniture and an adjoining kitchen-office that is filled with Durham’s handiwork and a number of Alves’s photos. The cabinetry is a collage of rare wood scraps surrounded by pea-colored tiles and funky assemblages (including a refrigerator fitted with curving planks of walnut, a purple-tinted photo by Alves, and bits of neon circuitry). A lime-green side table with three legs is buttressed with an antler painted bright blue, while a chandelier pieced together with tree limbs and scrap metals is festooned with a rainbow of broken Murano glass leaves and birds. Over a few coffees, he laughs as I tell him my GPS directed me to the graves of the Grimm Brothers in a neighboring cemetery and invites me to eat lunch with him and his fastidious German assistant, Kai Vollmer. Despite his health concerns — he traverses long distances with a walker — Durham’s piercing blue eyes are bright as ever and he manages to cut a sharp figure in a beige button-up, herringbone vest, brown trousers, and a cobalt-blue work coat you’d expect to find on Bill Cunningham. He speaks in a very considered, slow cadence and cooks with a similarly plodding purpose. In the kitchen he dices (and then boils) an octopus and some wild rice with cashews for a family-style feast before we take a leisurely stroll over to his nearby studio inside a former warehouse complex just down the street from the oldest bar in Berlin.

“I can cook, I can write letters, I can write poems. Whatever comes up comes up,” says Durham, who would prefer to spend most of his time at the converted leather factory he and Alves occupy in Naples, Italy. He’s currently making a hand-carved presepio for their Christmas nativity. “I never want to make things. I have a compulsion to live a good life.”

Still, the work drives Durham. In fact, he explains that he and Alves have only taken two vacations in their life together (both in the last decade when he started making enough money on his art to travel outside of work). “I can’t just lay on the beach,” he says, describing a trip to Puglia five years ago. “It was very nice to swim but it’s nice, too, to walk along and find some rocks, find some pieces of wood.”

While he considers his production of 20 to 40 physical works per year to be “art pollution,” he says he can’t stop objects from finding him — be it a felled branch or a box of partial animal skulls sent by a Vienna dealer. Three now stand sentry atop metal armatures in the corner of the sitting room and offer a window onto his latest solo show, “God’s Children, God’s Poems” (open through November 5) at Zurich’s Migros Museum of Contemporary Art. Representing some of his most ambitious work to date, the show features a herd of 14 massive assemblage sculptures that piece together a tinker’s trove of burnt wood, vintage furniture parts and entire wardrobes, saw horses, plaid blankets, Fair Isle sweaters, waxed-cotton jackets, blue plastic and steel piping, and old skulls (adorned with gemstones, industrial bolts, tanned leathers, and sprays of iridescent auto paint) from some of the largest extant animals to ever roam Europe, including a Polish bison, Great Dane, Norwegian musk ox, British Shire horse, and a Maremmana bull from Tuscany.

“I’m finished with animals,” says Durham, who employed a number of animal parts — even a human skull, to the dismay of Meredith and her cohorts — in his early Native-focused works featuring police barricades and semiprecious stones. After a leisurely walk, aided by his walker and some shouldering on my part, we arrive at his woodworking studio whose corners are overrun by a small forest of odd branches and stumps. A work table displays a collection of Murano glass bits and woodcarving tools. “I told Kai that when I finish the work I’m doing now I’m going to become a conceptual artist and not make things,” he says with a laugh. “But I cleaned out the studio and started making four new works.”

He leads me into a windowed room showcasing examples of some beadworks that may become part of Labinnac (that’s “cannibal” backwards), the design company he and Alves are establishing (it’s not out yet) to market the beadworks and furniture made by indigenous people in Brazil and Ecuador, giving all the profits to the workers and creating a scholarship fund. Durham did a similar thing with some dolls he made with children from the school he and Alves ran while in Cuernavaca, where he and Alves moved in 1987 after a year in Hoboken, in which he acquired a near-fatal case of amoebic dysentery from a bad water supply, and six years in New York. After a quick tour we drink tea in some lawn chairs on the loading dock of his studio and discuss his latest Stateside opponents.

“They want to disown me,” says Durham with a laugh. “I have a good friend in Canada that says this is a plague that is happening among all Indian communities in Canada and the U.S. that has nothing to do with tradition or authenticity, but then calls down on tradition and authenticity as though it were the law. So we join in our own oppression because it feels good. It’s a strange complicated setup where we participate in our own colonization as if it were freedom instead of colonization.”

After getting into the weeds of tribal sovereignty, he quiets down a bit then admits he’s unfamiliar with this new group. “I really don’t want to talk about this because if I say something, it’s ammunition for them to respond and that is what they desperately want,” he explains. “They want a public argument that I would join and they would rejoin so that they get more audience. In my mind no one ever wins an argument at all, there’s no winning or losing, there’s just stupidity.”

He will, however, offer his thoughts on the IACA. “This act is supposedly to save the Indian market of arts and crafts, but save from what?” he asks. “Competition by Koreans and Chinese? But all you have to do is say ‘Made by so and so of the Navajo Nation.’ You don’t need government approval for your arts-and-crafts movement. I think there’s more to it than that.”

The Whitney, for its part, appears to be caught on a high-wire, balancing between Durham and his detractors. “While we cannot speak for any other institution, we recognize that museums have increasingly become sites of political action and protest. The Whitney recognizes that we are a platform for public debate and discussion, and we welcome the exchange of ideas,” Elisabeth Sussman, who selected Durham for the 1993 Biennial, and Laura Phipps, the curators who organized the Whitney leg of the Durham show, wrote to me in an email. The Whitney, like the Hammer Museum, will not have any disclaimer about Durham’s identity in their exhibition texts.“The artist and the Museum preferred not to frame the exhibition in terms of the controversy surrounding his identity. We have definitely thought a lot about the framing of the show. We are thinking about Jimmie Durham as one of the most inventive American artists working today who has for the past forty years created work that considers and critiques the complexities of historical narratives and notions of authenticity.”

The museum will also be presenting two new, site-specific works of Durham’s: Homage to Alexander Calder No. 2, a marble dust and epoxy cast of an ancient Roman sculpture of Hercules that will hang from bungee cord and ankle harnesses in the stairwell; and a collage of the artist’s old selfies with an accompanying text, meant to critique imagery of the American West co-opted by Madison Avenue to sell cars and cigarettes.

“We are aware, of course, of the debates surrounding Durham’s self-identification as Cherokee throughout his life although he is not an enrolled member of a Cherokee tribe,” add Sussman and Phipps. “We do feel that it is important to acknowledge the questions that have been raised about Durham’s identity specifically, and we will address these issues in other forums, including through public educational programs and resources on our website.”

This seems like a measured, if obvious, approach. Especially after the Guggenheim removed three works involving animals from its landmark “Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World” survey before the show even opened in response to half a million animal-rights activists signing an online petition demanding the exhibition be “cruelty-free.” The move prompted severe rebukes from critics and artists (including Ai Weiwei, who curated the show’s video section) condemning the institutional censorship.

“This is human, and it’s called intolerance. It’s not about politics, it’s about lack of education, it’s about fascism and its old charismatic leaders again,” says Abraham Cruzvillegas, the renowned Mexican conceptual sculptor who has been friends with Durham since 1991, when they met at an exhibition for the cartoon artist Hêlioflores in the Borda Garden of Cuernavaca, where Durham and Alves lived from 1987 to 1994. (Today, the two are both represented by the Mexico City gallery Kurimanzutto.) “The real issue about this ‘controversy’ makes me fear nationalism. Whose roots are not rhizomatic and looped, crazy and delirious, as our DNA? Who doesn’t fake identity? We are all self-created characters, funky tricksters pretending to belong to something we don’t really understand properly, impersonating ourselves. Me, personally, I’m Muslim-P’urhepecha-Ñhañhu-Bayaka-Kichwa-Pigmy-Korean-Wirarika-Jibaro-Ikoot-Gâtiya pâin-Taino-German Jewish, born in Ajusco, but adopted Marseille as my country.”

In other words, even if Jimmie Durham is this big fraud, well, so fucking what? Over the past four months this is the literal response I got from almost every artist I spoke to — from mid-career semi-starving teachers in Berlin to blue-chip Angelenos, and yes, some of them were Native — when I raised the specter of Durham’s ancestral issues. One ascendant young Latin artist, who did not want to be named in this piece, even suggested, “If that’s true, and he faked it all, he’s the best artist since Duchamp. It’s like Rrose Sélavy on steroids.”

For the non-Dadaists in the art world, there is a more earnest critique of this position. “Part of Durham’s draw is his outspoken criticism of colonialism,” wrote America Meredith in a piece on “ethnic fraud” in Art in America. “What could be more colonial than non-Native curators and museums providing a platform for a European-American man living in Europe to speak on behalf of all indigenous peoples of the Americas? Native American people deserve the fundamental right to speak for ourselves, even within the art world.”

After a few hours of examining new works and sharing old stories in the studio, Kai drives us in his station wagon to an opening for one of Durham’s friends. The crowd is a Teutonic analogue to the Bushwick gallery scene and spills out onto the sidewalk. A small circle of neue hipsters forms around the man of the hour and his honored guest, who takes a seat on his walker and enjoys a few glasses of white wine, which will plague him overnight. When I arrive the next morning I find Durham in the same clothes. He hasn’t slept and nearly went to the hospital thinking he was having another stroke.

“I shouldn’t have had those glasses of wine without eating,” he says, and for a moment that pushes me off the subject at hand. But after some coffee and a quick lunch of chicken liver pâte, which he blends with curried vegetables, Durham offers a veiled anecdote about his first memories of being Cherokee. “When we were in school every child had to pledge allegiance to the flag, but they added the phrase one nation under god, and my mother said, ‘Don’t say that. Pretend to say it, get in trouble, but don’t say it.’ To all of us children she’d say, ‘Don’t give in to their nonsense,’” he says. “I never made a passing grade in my childhood, not once. I just would not look at the books, I wouldn’t do homework, wouldn’t do tests. I didn’t want to be part of it. I failed first grade. Just passive resistance.”

Some might argue that’s what he’s been doing to his opponents all along: ignoring them to death, refusing to play their game. “We have real pressing issues for Indian people in the Americas, in the U.S. especially,” says Durham. “Dire issues that have nothing to do with these things, they have to do with real rights.”

When I get back to the States, a half dozen more articles appear about Durham — some for, some against — so I ask him, as someone whose whole career in art and activism traded heavily in identity politics in the service of flipping the script on these so-called self-colonizers, does he even care to play that game now that the tables are turned?

“It is important to me,” he writes in a lone email. “I am Cherokee. BUT I AM NOT A CHEROKEE ARTIST. That difference means to me that I try to join up with artists throughout history who are artists, with no special claims beyond art, but also to claim art as the reason to make art.”

*The original version of this article incorrectly stated that America Meredith wasn’t familiar with Durham’s work before the present controversy.